After about nine months of crawling, rolling, and being schlepped around, most of us begin to take our first steps. From there, an insatiable drive propels us to strut about with our heads high, and we enter the exclusive—and sometimes bizarre—world of the biped.

There’s a lot more to it than putting one foot in front of the other. Here are three things about our two-legged approach that may surprise you:

1. There’s More than One Way to Walk

Let’s do a little experiment. Stand somewhere you have a clear path of 5-10 steps in front of you. Now, close your eyes.

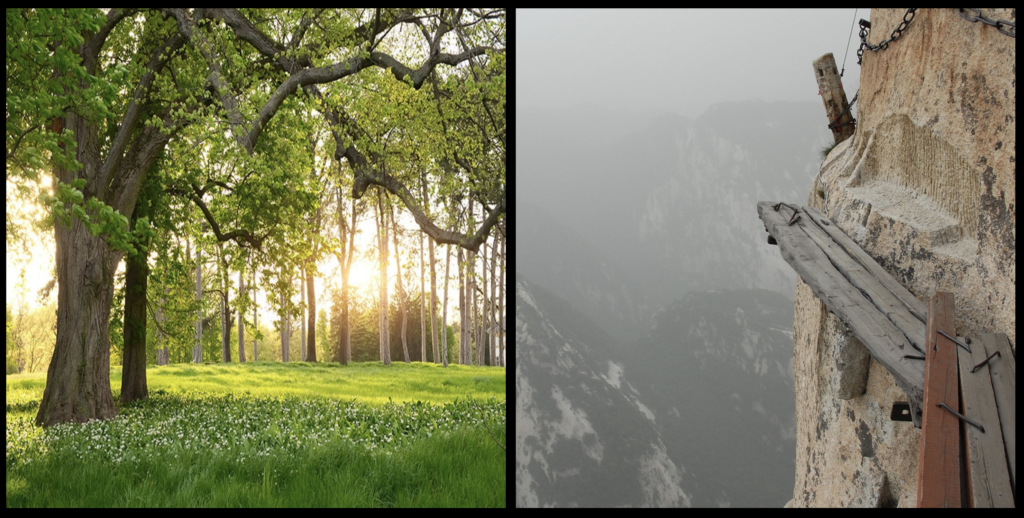

Imagine that you are standing in a grassy meadow on a spring day. Soft, fragrant earth is spread out before you while the sun warms your shoulders. Imagine walking through this meadow without a care in the world.

In your body, notice how your muscles respond to this imagery. What might this kind of stride feel like? Maybe even try taking a few steps through the real world. What do you notice?

Now, reset. Let’s paint a different picture.

Imagine you are standing on a rickety boardwalk through a high mountain pass. To one side of you looms a wall of stone, to the other, a steep drop off into an icy chasm.

Would you walk differently here than in the meadow? Can you feel the muscles in your body behaving differently as you imagine this frightening scenario? Again: if you like, take a few steps here in the real world. Can you feel a change?

The primary factor in how the body organizes is your perception of threat. When threat is low, we move one way; when it is high, we move another. The difference is plainly visible in how we walk.

Meadow walking (low threat) is characterized by pliable, adaptive muscles. The weight of the body draws down as we step forward, making firm, decisive impact on the ground with our feet. The arms swing easily, contributing to our momentum, interacting easily with our environment.

Mountain walking (high threat) is tense and rigid. Muscles brace against the prospect of impact, and limit potentially dangerous movements. The arms and shoulders lift, gripping the neck and head to avoid uncontrolled directional changes; footfalls become reaching and hesitant.

And it doesn’t require being in a sunny meadow or a menacing mountain pass to generate these states. The brain can perceive threat from a task at work, or a stressful situation at home. It can be frightened of people, or places, or memories.

You may be sliding in and out of these different types of walking without even realizing it, based on where you’re walking, and what you’re thinking about while you do it.

2. The “Push Off” Conundrum

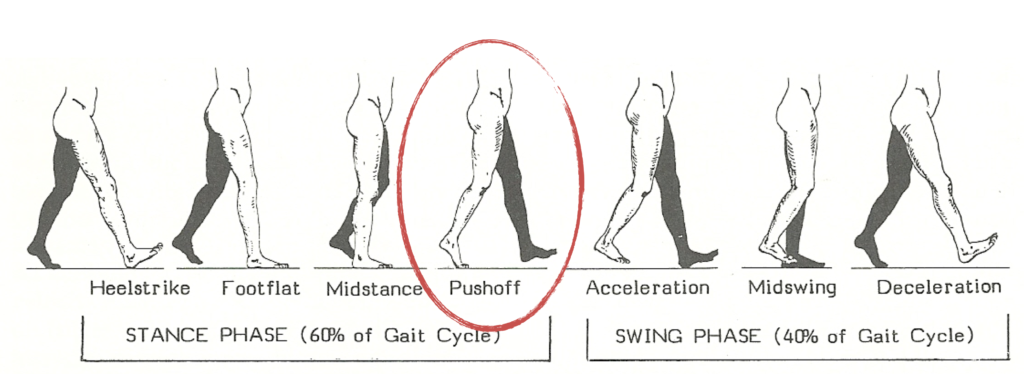

Take a look at that pair of legs I’ve circled. If you were asked to describe what that person is doing, “pushing off” might seem sensible.

But look again, and notice that the shadowed leg appears to be swinging forward while the other “pushes off.” That swing generates a lot of momentum: enough, in fact, to pull the body’s center of mass forward with it.

Pushing down against the ground can move you—but swinging your other leg forward can move you, too. So which one are we actually doing?

That all depends on our perceived level of threat.

When you push into the ground behind you, your muscles are doing double duty: stiffening to press up and away from the ground—but also hanging on, so that, if going forward turns out to be dangerous, we can slow down, or stop.

Pushing off is part of high-threat “mountain walking.”

Swinging forward is for low-threat scenarios. The rear leg remains pliable, and rather than pushing you up and away from the ground, ever so slightly drops you toward the ground, adding gravity’s pull to your momentum. Your movement forward is faster, and more decisive.

The benefit of swinging forward is that your pliable muscles can absorb a lot more of the impact of your next step, turning it into potential energy to fuel more steps. By contrast, “pushing off” uses up a lot of energy literally holding you back while it drives you forward.

The easiest way to see which kind of walking you’re engaged in? Watch how your knees behave.

If the front leg stiffens at the knee when it hits the ground, so that you float over a straight leg, that’s mountain walking. You’re perceiving threat, and that stiff knee is preparing to reel you back in. On a long enough timeline, that stiffness may start to hurt.

If your knee flexes or softens slightly upon impact, you’re meadow walking. This generates faster, more decisive motion at a lower energetic cost.

This method is more comfortable, and easier on your joints, but be aware: you may find that you notice physiological responses to stress or apprehension in this state.

3. Biped Bar Trivia

Humans are always looking for ways to gloat about how special they are, and we lean on bipedalism as one of the things that sets us apart. But: nature has come up with lots of ways to amble about on two feet:

- Almost all apes are capable of bipedal ambulation, and even one species of monkey, the Japanese macaque, can be trained to be remarkably proficient as a biped.

- Birds are all bipeds, technically. In fact, the African ostrich has the honorable distinction of “fastest creature on two legs,” with a top speed of 43 mph. They can even “jog” at 30 mph (that’s two mph faster than Usain Bolt‘s top speed!) for up to half an hour.

- Over 50 species of lizard dabble in bipedalism, including the Basilicus basilicus, that can run bipedally—on water.

- There are several bipedal hoppers out there, too, like kangaroos, who walk on four limbs, but jump with two when they really need to move.

- Even cockroaches flirt with bipedalism at their top running speeds—at around 50 body lengths per second.

Leave A Comment:

Your email address will not be published.