As a child, my daughter loved to play with blocks. Her creations varied wildly in color and orientation. Sometimes they had patterns, other times they were completely chaotic.

And: almost all of them were fragile. Most couldn’t stand on their own and would often fall apart moments after being created.

These observations didn’t register as meaningful until we began foster-parenting a second child. The child, who I’ll call Mary, came to us from a deeply insecure environment. The first time the two children played blocks together, and called me in to show off their work, the meaning that hides in play hit me hard enough to catch my breath.

As usual, my daughter’s tower was chaos: multiple spires of random heights, the telltale explosion of color, and the total inability to stand on its own.

Mary’s block creation could not have been more different: every block was the same color: a near-perfect rectangle that stood steady on a wide base.

Looking at the two of them standing there with their creations, I realized that what I was seeing was not random. Each child was holding an expression of the world as they saw it.

My daughter’s tower was an observatory: a meandering exploration of balance that is only possible when you know that it can all come crashing down and you’ll still be ok.

Mary’s was a fortress: an acknowledgement that, when the world is unstable, you have no choice but to build something stable of your own.

In a particularly powerful moment, the two girls noticed that if one structure could be attached to the other, they could both stand taller and more beautiful than before:

So, why on earth are you reading about this on a blog about human movement?

Because someone on our Facebook page asked me about the rotator cuff, and this is just how my brain works.

The internal rotation of the humerus at the shoulder, which is an essential part of the throwing action, is the fastest motion the human skeleton is capable of producing. How fast? Go ahead, take a guess.

Nope, faster. Much faster: 9000 degrees per second, to be exact. For reference, that’s how fast the tires of a standard sedan turn—if you’re traveling at 120 miles per hour.

This power comes at a cost. It takes years for the brain to learn the shapes and properties of the tender structures of the glenohumeral joint, and to develop the software necessary to use such impressive hardware safely. The brain must be able to explore for this process to work.

What my daughter did with her blocks is, in fact, exactly what her brain—and mine, and yours—does with shoulders, elbows, wrists and fingers. They are made for exploring, and the patterns the brain makes out of what it finds are constantly being updated, refined, and extrapolated.

But they are not independent structures, your shoulders. All that power, and the exploration it takes to generate it, has to be be based on something: something big, geometrically solid, sturdy . . .

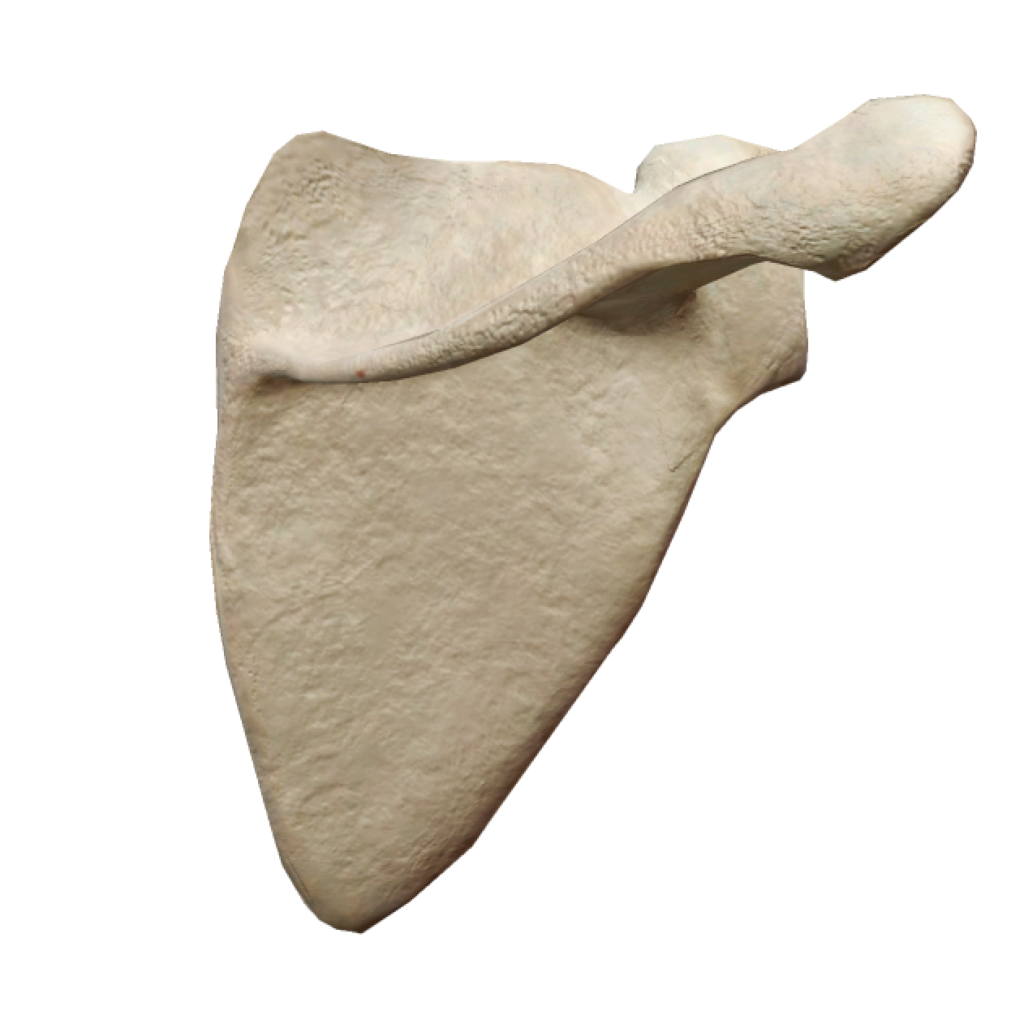

OH, DO YOU MEAN THIS GIANT TRIANGLE OF SOLID BONE THAT LIVES ON YOUR BACK?

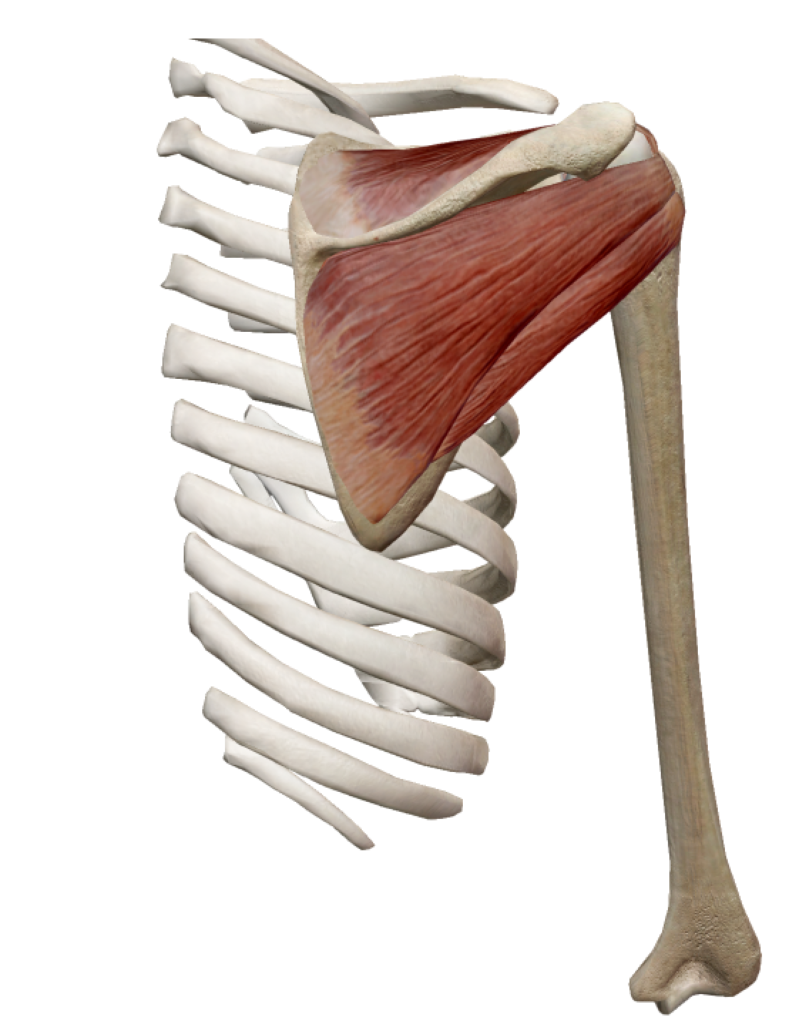

This is your scapula. Surrounded by some of the thickest, strongest, longest muscles in your body, it’s the fortress in which your fragile shoulder lives.

When my daughter built towers, she built them fragile because she could feel that her explorations were anchored. There’s nothing that could happen to her tower that couldn’t be buffered, and managed. Mary couldn’t feel that, so she built it.

Do you know what happens when the shoulder begins to feel like Mary did? That there’s no support, no connection to external strength? It does exactly what Mary did: it builds it.

We call this frozen shoulder. We call it bursitis, or tendonitis or impingement. We have lots of fancy names for it, but it’s all the same thing: the brain can’t trust that the shoulder’s explorations are safe, and so it toughens the surrounding muscle. It builds its own fortress.

It will get you through the day, but it’s no way for a shoulder—or a child—to live.

The rotator cuff, then, is one of the most beautiful arrangements in the body, because it’s how the scapula tells the shoulder: “I’m here, and I’ve got you.”

“I’m here, and I’ve got you.”

Rotator cuff dysfunction is scary, and it hurts—and thicker, stronger muscles are not always the answer. We’re quick to classify someone’s rotator cuff as “weak” when I think a better description is “frightened.” This is not a metaphor. Establishing emotional barriers to potentially damaging ranges of motion is why you have a central nervous system.

Treatment is about creating spaces where clients (and their shoulders, and necks, and fingers, and spines, and feet) feel safe—and then challenging them to explore. Their own nervous system will do the rest. Your gym, your clinic, or your office is not where you make your clients tougher; it’s where you allow them to be fragile.

Leave A Comment:

Your email address will not be published.