Physical distance is one means of keeping people apart, but not the only one—nor is it the only way of bringing people together.

As you wrestle with the approach of meaningful holidays, both social and spiritual, and how the worldwide pandemic might affect them, consider that there are two problems in the ring with you. Your best chance at beating them is telling them apart.

The first problem is that this—*gestures to everything*—hurts.

Put aside your daily mantras to stay positive. For just a moment, consider that your sadness and frustration aren’t the result of failing to be grateful, disciplined or enlightened. Regardless of what you believe about covid, race, the news, the election, or any other of a long list of challenges, you can feel the discord of these times: the fractured, painful, uncertain disarray of it all.

Of course, you need to pick yourself up and carry on in spite of these woes, but if you are to be successful at that for any length of time, you have to be honest—at the very least to yourself—about the fact that it hurts.

Once you commit to that honesty, what you feel in your body and what you are willing to accept as true get closer to being the same thing. There is profound comfort in letting yourself know that you’re not crazy. Stomach sinking in despair? Heart racing with fear? Don’t waste a moment telling yourself it shouldn’t. Too late, it already is! If you own it, you are relieved of the distasteful duty of convincing the part of you that feels it that those feelings are wrong.

The second problem in front of you is that people need to believe they share a common experience in order to feel connected to one another. We all crave the validation of having our truth reflected back at us, and the security of knowing that others live in the same world we do. Are the people around you ready to face the same threats that frighten you? Do they have the ability to provide—or even understand the things that you find comforting? These basic commonalities are rich soil for fruitful relationships.

Physically being in the same room with someone is a powerful way to generate common experience: we smell the same baking pies, we hear, and laugh, at the same old jokes—even being part of the same dysfunctional conflicts can, ironically, brings us that sense of shared experience.

But it is not actually, physically, being in the same room that connects you. It’s all the myriad little ways we demonstrate that: “yes, we see the same world, and I’m here to face it with you.” Shared physical space may be how you are accustomed to expressing this heartfelt sentiment, but it is not the substance of that sentiment. Sharing your world with someone does not require that you share a room.

And so, with two problems now understood, one solution emerges.

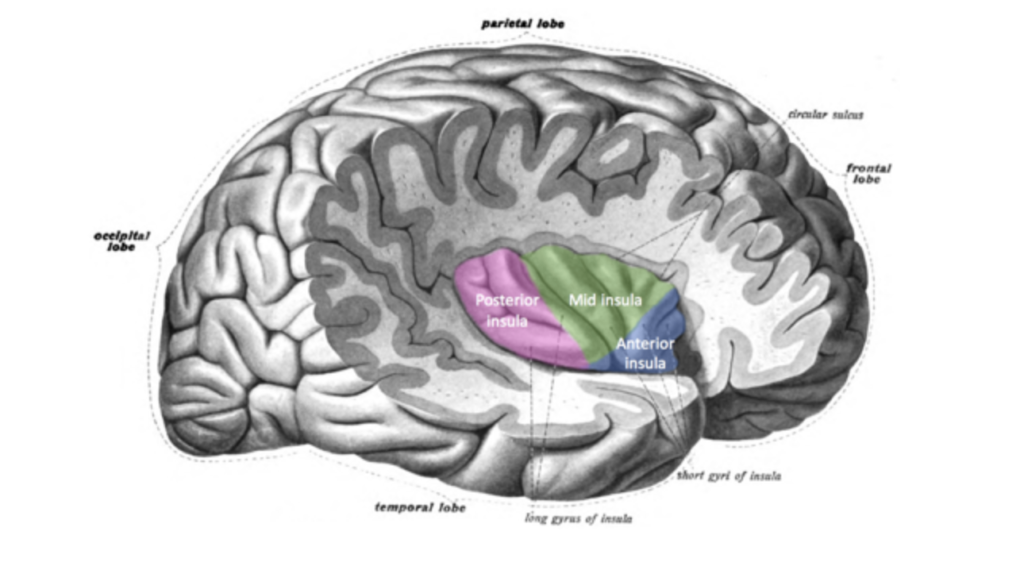

Commitment to an honest evaluation of your struggles—to the real joy and suffering you feel in your body—makes you more empathetic. It’s a measurable phenomenon. It means that you are prepared to listen as those close to you express their fears and misgivings about—*gestures to everything*—this.

And, just like that, you’re both living in the same world, seeing it for what it is, ready to face it together.

This shared experience can happen across town, or across an ocean. Things are hard everywhere. You don’t need to smell the same pie; you can both heave a despondent sigh over the phone at the pie neither of you will smell this year. It’s a loss, of course, but it’s shared loss, and that is togetherness of an immensely important kind.

Whether or not to travel and gather may sound the like the question everyone is wrestling with right now, but listen closer. What we’re all asking is: “how can I share my world with you, and can we be honest with each other when we do?”

Show courage in answering these questions and nothing whatsoever—not even distance—can keep you apart.

Leave A Comment:

Your email address will not be published.